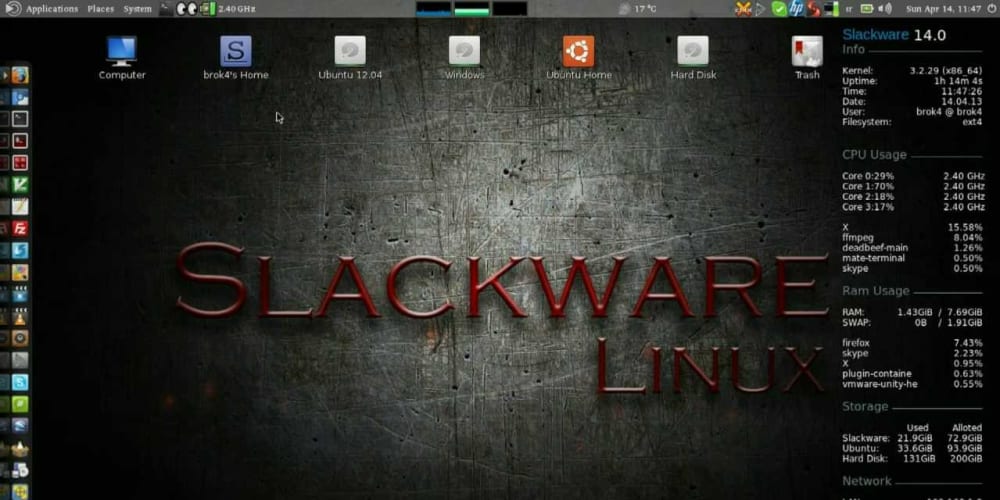

Making The Case For Slackware In 2018

A review by Tom Nardi from https://hackaday.com

If you started using GNU/Linux in the last 10 years or so, there’s a very good chance your first distribution was Ubuntu. But despite what you may have heard on some of the elitist Linux message boards and communities out there, there’s nothing wrong with that. The most important thing is simply that you’re usingFree and Open Source Software (FOSS). The how and why is less critical, and in the end really boils down to personal preference. If you would rather take the “easy” route, who is anyone else to judge?

Having said that, such options have not always been available. When I first started using Linux full time, the big news was that the kernel was about to get support for USB Mass Storage devices. I don’t mean like a particular Mass Storage device either, I mean the actual concept of it. Before that point, USB on Linux was mainly just used for mice and keyboards. So while I might not be able to claim the same Linux Greybeard status as the folks who installed via floppies on an i386, it’s safe to say I missed the era of “easy” Linux by a wide margin.

But I don’t envy those who made the switch under slightly rosier circumstances. Quite the opposite. I believe my understanding of the core Unix/Linux philosophy is much stronger because I had to “tough it” through the early days. When pursuits such as mastering your init system and compiling a vanilla kernel from source weren’t considered nerdy extravagance but necessary aspects of running a reliable system.

So what should you do if you’re looking for the “classic” Linux experience? Where automatic configuration is a dirty word, and every aspect of your system can be manipulated with nothing more exotic than a text editor? It just so happens there is a distribution of Linux that has largely gone unchanged for the last couple of decades: Slackware. Let’s take a look at its origins, and what I think is a very bright future.

A Deliberate Time Capsule

It’s not as if it’s an accident that Slackware is the most “old school” of all Linux distributions. For one, it’s literally the oldest actively maintained distribution at 24 years. But more to the point, Slackware creator and lead developer Patrick Volkerding simply likes it that way:

The Official Release of Slackware Linux by Patrick Volkerding is an advanced Linux operating system, designed with the twin goals of ease of use and stability as top priorities. Including the latest popular software while retaining a sense of tradition, providing simplicity and ease of use alongside flexibility and power, Slackware brings the best of all worlds to the table.

For those of you not up on your Linux distribution buzz-words “stability” and “tradition” could here be taken to mean “old” and “older”. Cutting edge software and features are generally avoided in Slackware, which is either a blessing or a curse depending on who you ask. A full install of the latest build of Slackware could potentially have software months or years out of date, but it will definitely have software that works.

The upside of all this is that things more or less stay the same in Slackware-land. If you used Slackware 9.0 in 2003, you’ll have no problem installing Slackware 14.2 today and finding your way around.

Benefits of Simplicity

If you’re looking to learn Linux, there’s great benefit in Slackware’s almost fanatical insistence on simplicity. Rather than learning a distribution-specific method of accomplishing a task (a common occurrence in highly developed distributions like Ubuntu), the “Slackware way” is likely to be applicable to any other Linux distribution you use. For that matter, much of what works in Slackware will also work in BSD and other Unix variants.

This is especially true of the Slackware initialization system, which is closely related to the BSD init style. Services are controlled with simple Bash scripts (rc.wireless, rc.samba, rc.httpd, etc) dropped into /etc/rc.d/. To enable and disable a service you don’t need to remember any distribution-specific command, just add or remove the executable bit from the script with chmod. Adding and removing services is extremely simple in Slackware, making it easy to set up a slimmed-down install for a very specific purpose or for older hardware.

Speaking of keeping things simple, the controversial systemd is nowhere to be found. In Slackware, the text file is still King, and any software that obfuscates system configuration and maintenance is likely to have a very tough time getting the nod from Volkerding and his close-knit team of maintainers.

Finally, one of the best features of Slackware is the avoidance of custom or “patched” versions of software. Slackware does not apply patches to any of the software in its package repository, nor the kernel. While other distributions might make slight changes or tweaks to the software they install in an attempt to better brand or integrate it into the OS as a whole, Slackware keeps software exactly as the original developer intended it to be. Not only does this reduce the chances of introducing bugs or compatibility issues, but there’s also something nice about knowing that you’re using the software exactly as the developer intended it.

Frustration Free Packaging

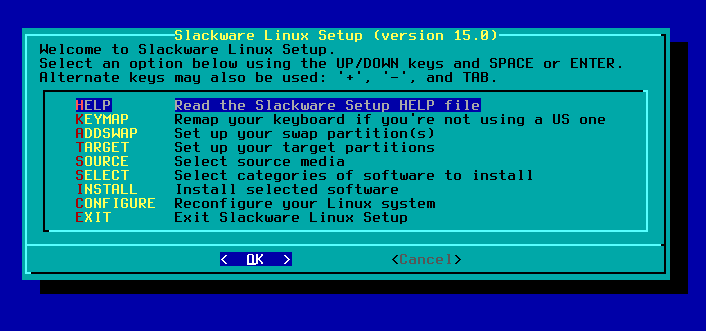

If you’ve heard anything bad about Slackware, it’s almost certainly been about the software packages. Or more specifically, the lack of intelligent dependency management. In other distributions, the package manager understands what software each package relies on to function, and will prompt you to install them as well to make sure everything works as expected. There is no such system in Slackware, but that is also by design.

In an effort to make things as simple as possible, the expectation is that you install everything. Slackware is developed and tested with the assumption that you have a full installation of every package in the repository. In fact, this is the default mode for the Slackware installer; you have to switch into “Expert” mode if you don’t want everything.

If you don’t want a full install and would rather pick and chose packages, you are free to do so, but you’ll need to manually handle dependencies. If you get an error about a missing library when you try to start a program, it’s up to you to find out what it depends on and install it. You’ll quickly develop a feel for just what is and isn’t required in a Linux system by going through and manually solving your own dependencies, which again comes in handy if you are trying to tailor-fit an OS to your specific requirements.

Should You be Slacking?

Today, the argument for Slackware might actually be stronger than its been in the past. By not embracing the switch over to systemd, Slackware is seeing more attention than it has in years. It’s still unclear if it can avoid systemd forever, but at least for the foreseeable future, Linux users who aren’t onboard with this controversial shift in the Linux ecosystem have found a safe haven in Slackware.

Slackware was my first Linux distribution, and today I still recommend it to anyone who’s looking to really learn Linux. If you simply want to use Linux, then I have to concede Ubuntu or Mint is probably a better starting point for a Windows-convert. It’s the difference between learning how and why your operating system works, and having the OS leave you alone so you can work on something else. Not everyone needs to learn the former, but it may help you in the future if the latter falls on its face.